I recently completed a book titled “Kariba: The Struggle with the River God” by Frank Clements, which was published in 1959. It provides an account of the trials and challenges faced during the incredibly ambitious project of building a dam in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). It was an interesting read, however before I could fully comprehend the magnitude of their task I needed not only to remove from my mind the magnificent image of the lake that I am familiar with today, but also to put myself in the frame of mind of those times.

The initial idea of harnessing the life generating power of the mighty Zambezi River dates back as far as 1914 (by some accounts even further) when the Kariba Gorge was identified as the ideal location to dam the river. The dream to build a hydroelectric dam finally became a reality when construction commenced in 1955. My thoughts immediately drift to my mother, at the time she would have been just two years old, toddling around the garden of her Salisbury (now Harare) home. The fourth of four siblings born to South African parents in Southern Rhodesia, their generation would be among the first to delight in the beauty and excitement offered by Lake Kariba in the years to come.

The word Kariba refers to the rock that jutted out over the gorge which was believed to be the resting place of the River God Nyaminyami. It was also the location chosen to build the dam wall and thus the name “Lake Kariba” came to be.

The tender was awarded to Italian engineering company Impresseti because the proposal was the cheapest while still being seemingly feasible. Clements gives factual accounts of the various stakeholders involved, the Italians, French and other Europeans who arrived in primitive Southern Africa. The Northern and Southern Rhodesians of English and Afrikaans descent, who had moved north from South Africa in the hopes of establishing wealthy new beginnings, and of course, the local tribes of the region. The benefits that would result if this ambitious engineering monstrosity was achieve: 1500 megawatts of power, ample irrigation for what promised to be productive fruit farms developed on the shores of the lake and a magnitude of abundant fishing.

Work on the dam wall June 1959. Photo: Kariba – Frank Clements

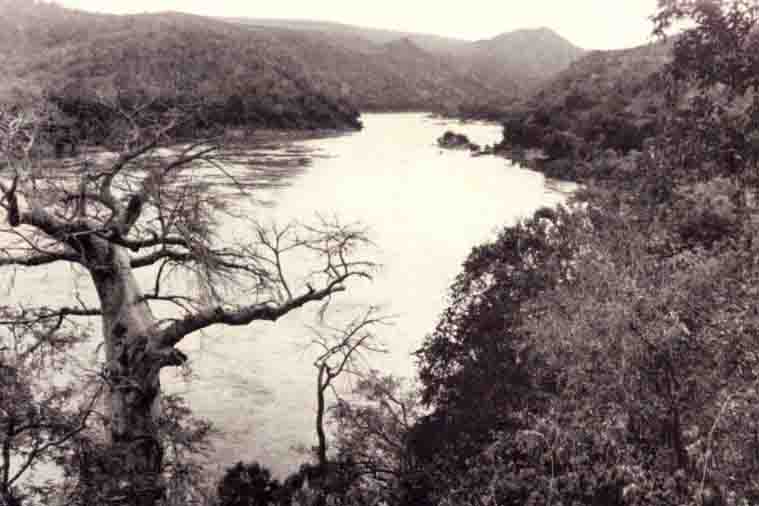

The everyday descriptions of the landscape and wildlife fascinate me, “The middle reaches of the Zambezi flowed through a country ‘where only birds can fly or serpents can crawl’.” I try to picture the density of the bush, combined with the plentiful population of tall mahogany and baobab trees, all of which would be flattened to the ground before the waters could rise to cover any remains of their existence.

The progress of mankind came with a detrimental cost to many, but none more so than the native inhabitants, the Batonka tribe. These communities were forcibly relocated to harsh landscapes with little or no access to food and water. Cultural beliefs and traditions almost completely forgotten as the deserted remains of their mud and thatch huts dipped below the water line forever. Thousands of the young tribesmen were lured into the construction of the wall with the promise of meagre

remuneration as well as board and lodging in return for 12 physically draining hours of manual labour. At the time it was an attractive offer for those who were left with nothing but the faith that perhaps their loyalty to the River God, Nyaminyami, would see them prosper in this life or the next.

Many local people at the time believed that the act of damming the Zambezi River would so enrage Nyaminyami, that he would cause the water to boil and destroy anything in its path. With this in mind I recall my mother sharing stories she remembered hearing, about the men who died at Kariba.

Some washed away by the river in flash floods, some snapped up by chancing crocodiles and others buried alive under quick drying concrete, where their bodies, some say, remain to this day. I wonder, was this, the totality of Nyaminyami’s revenge, or does he still brood beneath the surface, planning his next move?

Clements’ accounts of the abundant wildlife which roamed the bush are another dreamlike tale. I picture herds of elephant effortlessly clearing their paths through the dense bush, before the fear of gun wielding men was ingrained into their conscience. Rhino were abundant, with horns longer than a man’s torso and scores of antelope, monkeys, birds and reptiles filled the landscape. Nights were kept alive by the thrilling sounds of big cats on the hunt.

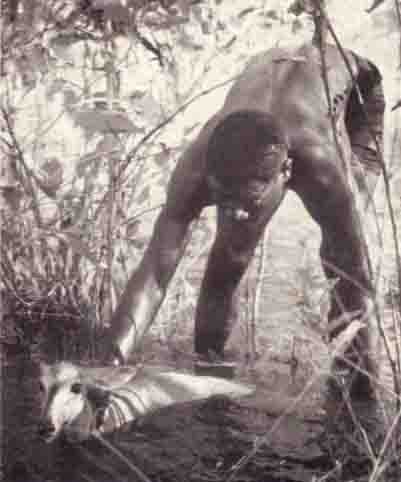

Project Noah saving a water buck and duiker. Photo: Kariba – Frank Clements

There are no official numbers that reflect the countless creatures that lost their lives during the years of construction, only gruesome recollections of animals clinging to life atop trees until they succumbed either to starvation or the rot that set in after being submerged in water for extensive periods ate away at their bodies. The suffering and torture of wildlife was only thinly masked by the heroism of a few gallant men who launched a rescue program which came to be known as “Project

Noah”. A romanticised tale which was not nearly as successful as our generation would like to believe. Nothing should be taken away from the brave acts of these men, who risked their lives showing great valour to rescue approximately 3 000 living creatures. How many animals were not so fortunate, we will never know.

Flash forward to the glimmering waters of Lake Kariba that I have come to know, it is still evident that nature’s balance has been tipped. Local communities are still struggling more than 60 years later to provide for their families and secure a fruitful life. Walking through the streets of dilapidated villages, one still hears the pleas to Nyaminyami to return and rescue his people. Wildlife populations were so depleted that species like the rhino became completely extinct from the area.

Bumi Hills safari Lodge provides incredible views of this inland sea. Photo: African Bush Camps

However, it is not all doom and gloom, we can’t deny the benefits generated by this momentous feat of engineering to the progression of man, and while we can’t change the negatives of the past we can plan for the positives of the future. In the last decade conservation efforts have been highlighted as a priority, and an informed and knowledgeable generation realises the need to restore the equilibrium. Financial investments into communities, conservation and tourism have seen a shift towards restoring the balance between man and nature.

National Parks and reserves have secured the safety of wildlife, and modern heroes take up the battle to defeat wildlife poaching, and mitigate human wildlife conflict while empowering the descendants of the original Batonka tribe. Great results have been achieved recently, elephant herds have increased in numbers, masses of buffalo graze the water’s edge, 2019 saw the return of cheetah to the area and research is underway to determine the feasibility of reintroducing rhino too. Zimbabwe is a leader in rhino conservation and has started seeing an increase in populations since 2018.

A safe haven for wildlife to flourish once more. Photos: African Bush Camps

As a tourist to Lake Kariba I feel the power of Nyaminyami, as the legend goes he was not defeated by the successful construction of the dam, but instead he has changed form and is now the power that runs along the cables supplying energy to surrounding communities. It is his energy I felt while watching elephants bath in the lake, or listening to pods of hippos grunting their laughs at jokes told amongst themselves, or tracking a leopard’s trail through the recovered bush.

A handful of beautiful lodges and house boats grant accessibility to this powerful place. Visitors from around the world gaze on in awe at man’s ability to create, destroy and recover. I find myself reminiscing about my days sitting at the historic Bumi Hills Lodge perched above the lake, as I looked over the expanse of water and wildlife reaching to the horizon, I had to commend us, humankind, on our ability to recover.

Amongst all that beauty I could clearly recall my mom’s words, “Your grandmother always said, ‘When we push nature too far she always finds a way to rectify the balance’.” Nyaminyami after all was never defeated. He was merely giving us time to learn our lesson.

The progression of man should never be at the expense of nature.

Thank you for joining the journey

– Gemma